“Whatcha watching?” I asked my daughter.

“a cooking show,” she said. She gestured at the television. “I think he’s a famous actor or something.”

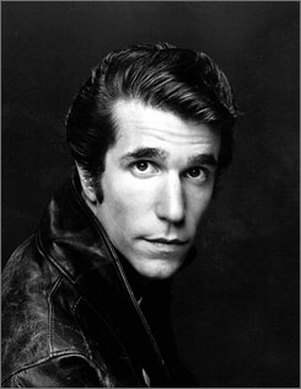

I looked at Henry Winkler, and then I looked at my daughter.

“Uh, yeah,” I said, trying not to sound too patronizing. “He’s The Fonz.”

My daughter just stared at me.

How do you explain The Fonz to a nine year-old in the 21st Century?

How do you put into words the wonder, the mystery, the unexplainable “cool,” of The Fonz?

The detachment? The Fluidity? The Zone?

How do you explain The Inexplicable Zen of The Fonz?

Answer: You don’t.

Not only could I not articulate the significance of Fonzie’s contribution to what it meant to be cool, detached, masculine, completely in tune with your universe, but I had to admit that, when it came down to it, even Richie, Potsie, and Ralph didn’t really understand it, either.

For them, the key word was acceptance.

When I was thirteen, which was exactly three hundred and fifty years ago, I sat in front of the television, saw Fonzie snap his fingers, and watched as girls emerged from the woodwork of Arnold’s and swarmed around him, hanging on his black leather jacket as if he had used a bug sprayer to fill the room with his pitch-perfect pheremones. As if that weren’t enough, Fonzie’s office was a burger joint rest room. He sanctioned the activities in his world by simply raising a thumb. He intimidated bullies with a twitch of his lip. He made the joint jump with music with just a slight tap of fist on the jukebox. He could articulate thirty-seven different messages through the manipulation of the single syllable, “Ayyyyy.”

The Zen of Fonzie’s abilities bordered on Magic.

Fonzie was the zenith of detached, unemotional masculine coolness, and I wanted in. So as I sat there in 1976 eating popcorn in my bean bag chair, I thought “that’s the job for me.”

But life, of course, is never that simple.

Fonzie–which is an abstract essence that exists in the cosmos and is not to be confused with Arthur Fonzerelli who worked at the local garage, talked politely to Mr. C., and lived above the Cunningham’s garage—knew most or all of life’s secrets and wasn’t talking. He could fix cars, seduce women, and pilot a mean-looking motorcycle without breaking a sweat or a smile.

All the boys at my school wanted to BE the Fonz, while all the Girls merely wanted to TAME him.

One night at a time.

There was no one like The Fonz before Happy Days, and there has been no one since. He is one of those rare, one-of-kind icons, a unique definition of certain kind of manhood. Not necessarily the kind you always want to exhibit, but the part of your manhood you want to exhibit when the “nice guy” approach isn’t working.

You want to be The Fonz when the guy cuts you off in traffic, when the neighbor blocks your driveway with his RV, when the drunk guy at the party comes on to your wife. You don’t necessarily want to resort to violence, but you want the other guy to know that, if it came down it, you might. All American men my age would like to think we still have a smidgeon of the Fonz inside us.

And needless to say, The Fonz would never use the word, “smidgeon.”

And even though I could have done without the black T-shirts, the teaching credential, the precocious daughter figure (although I currently possess all of these), and even though I could certainly live the rest of my life without ever again hearing the expression “Exact-a-mundo,” The Fonz still is one of the earliest expression of a kind of Zen masculinity from my childhood that I sometimes summon to help me navigate through this morass we call life.

Now that I’m living in the suburbs in a master planned community complete with block parties and HOA fees, and the neighborhood kids call me Mr. T. (a much sillier corruption of Mr. C. thanks to that other 70’s phenomenon, The A-Team), I’d almost forgotten what The Fonz had meant to me. The possibility of developing a sense of masculine Zen so cool and icy and confident that a simple “thumbs up” communicates your approval now seems so quaint and out of reach. Nevertheless, I was glad for the opportunity to tell my young daughter about the nature of The Fonz, even it was tough going.

“He played a character called The Fonz,” I said, as Henry Winkler shuffled around Paula Dean’s studio kitchen. As always, he seemed like a really nice, unassuming guy.

“Fonzie was really cool.”

That doesn’t seem to cover it, so I elaborate.

“Uh, really cool.” She stares at me again. I exhale. This time I use my hands for emphasis.

“No,” I said, flailing my arms. “ I mean really, really cool.”

She goes back to watching Paula Deen bake something.

It’s impossible. I give up.

Quite simply, The Fonz is just The Fonz.

You can’t put it into words.

And over time, he has reached the maximum essence of Zen Fonzie-ness.

In the end, you don’t really have to understand it.

Like Zen – and all great truths in life – it just is. TZT